Wood, mud, and other natural building materials are enjoying a resurgence as more sustainable alternatives to traditional materials. And while concrete can’t be avoided, could we reformulate it to reduce its carbon emissions?

Travel to Skellefteå, amid the forests and lakes of Northern Sweden, and you’ll soon notice the Sara Cultural Centre. Its 20 storeys rise above the city’s spruce trees; its windows caressed by the winter sun, its sand-colored walls glinting in the snow.

But beyond its handsome design, this museum, library, theatre, and hotel is special for what it’s made of. Reviving a building tradition with deep regional roots, the Sara Cultural Centre is shaped from wood, even as it soars some 75 meters above the town.

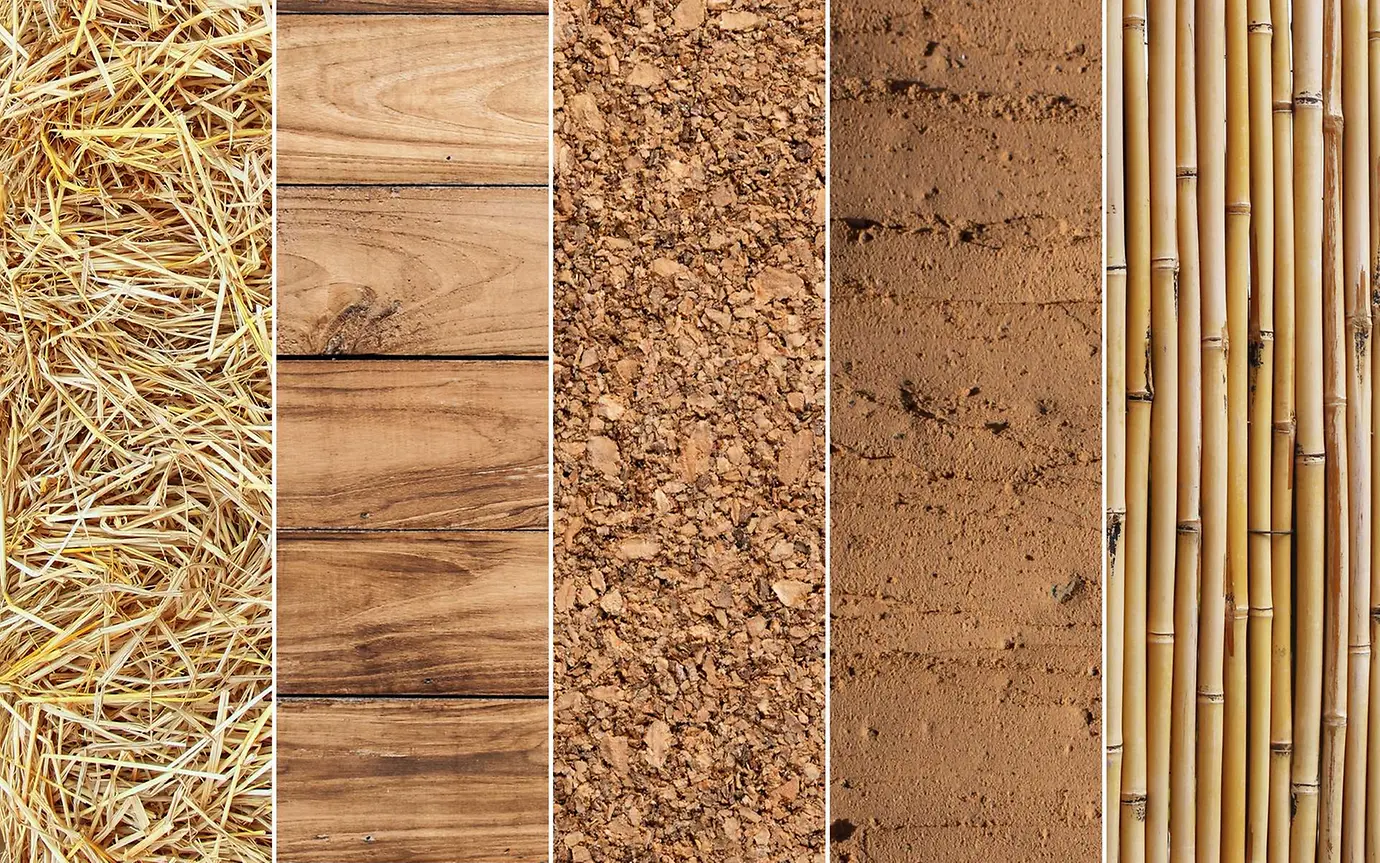

Nor is the marvel at Skelleftea, around 600 kilometers from Stockholm, particularly unique. On the contrary, the pressures of climate change, combined with the aesthetic power of the natural environment, are spawning dozens, even hundreds of Saras, in materials as varied as straw bales and cork.

Still, the future of architecture may not be completely natural. For if wood can do much to reduce the extent of climate change, researchers are equally busy boosting the sustainable qualities of concrete, which is just as well, given its vital importance to engineering projects of all kinds.

Humans have long exploited nature’s gifts to build their homes and public buildings. As far back as the Roman Republic, to give one example, the architect Vitruvius advised his readers to avoid cutting down trees in the spring, because their "looseness of texture" made them ill-suited as timber.

But if buildings made of wood and mud were stalwarts of Western construction for millennia – and are still popular in more remote corners of the planet – recent decades saw them all but disappear. "People began using more cement," explains Rikki Nitzkin, an expert in straw-bale building and member of the European Straw Building Association. She suggests that the cataclysms of the twentieth century may have caused ancient construction methods to be forgotten.

In more recent decades, however, straw and its cousins have enjoyed a revival across Europe. This is clear from the statistics. According to one 2019 estimate, there were around 5,000 straw-walled buildings in France, with 500 more going up each year.

Timber building is experiencing a similar resurgence. Thanks to an EU-funded project, towns as varied as Trento (Italy) and Brasov (Romania) are developing their own wood-building programs.

For Jessica Becker, of Wood City Sweden, the reasons for this uptick are clear. "It’s a renewable resource, so we have the opportunity to regrow the material," explains Becker, who promotes timber construction across the country. A fair point: Sweden now boasts twice the trees it had a century ago.

The idea of building with straw is intuitive

Rikki Nitzkin Strohbau

And as Becker points out, there’s the "double effect" of carbon removal. Once again, the numbers are illuminating. According to one 2021 study, every cubic meter of wood sequesters about a tonne of CO2, while straw-bale construction offers similar results. The same claims can be made of cob – essentially packed straw, mud and water – as well as cork and bamboo.

By way of comparison, the chemical reaction that produces a single tonne of traditional cement unleashes about half a tonne of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Listen to Rikki Nitzkin talk about straw building and her passion will quickly envelop you. "Something clicks inside," is how she puts it. "You discover that something about the whole idea of building with straw just attracts you. I don’t know how to explain it – it's intuitive."

Beyond their environmental advantages, perhaps the greatest strengths of straw, cob, and other natural materials are their aesthetic possibilities, and the way you can take them from the earth and create something elegant and new.

The Sara Cultural Centre is only the start. Consider, for instance, the Maya Boutique. Here, in the mountains above Zermatt, architect Werner Schmidt has built a marvel in straw, a building that feels as solid as any stone chalet – but which is ultimately made from cattle fodder.

Other natural structures slip into the environment just as gracefully. In Portugal, the Cork House positively burrows into the surrounding olive groves. In the Devonshire hills, one man built himself a cob house that feels like it was conjured, fully made, from the local gorse bushes and sheep fields.

Not that amateurs can just start cutting down trees or churning up dirt. As last century’s annihilation of straw construction implies, training is vital to success, especially when the materials involved are natural. By way of example, Nitzkin, who has made a career of teaching her craft, stresses that straw builders should be careful to compress their bales to avoid the mold that loose straw can encourage.

Beyond these practical challenges, even nature enthusiasts concede that man-made steel and concrete can’t ever vanish entirely. As Becker puts it: "We still have to use concrete for infrastructure and other buildings."

Jason Ideker agrees. As the Oregon State University professor and concrete expert emphasizes, everything from sewage facilities to pavements need to be made from durable, water-resistant materials, and wood or cork simply couldn’t cope.

Scientists are battling to improve concrete's carbon footprint

Jason Ideker, Professor at Oregon State University

Fortunately, there is progress here too. While it may not be quite as sustainable as cob, Ideker describes how scientists have battled to improve concrete’s carbon footprint. Limestone is at the heart of this. An important ingredient of Portland cement, one of the most popular types worldwide, manufacturers have traditionally added limestone to the kiln before firing – a process that decidedly increases CO2 emissions.

As an alternative, however, Ideker says you can add ground limestone after firing. And by combining it with other ingredients like calcined clay, you can create a product that cuts emissions by around a tenth.

Already common in Europe, Ideker says this approach is quickly being adopted by US builders, adding that ground limestone is both economical and available "pretty much anywhere on the planet."

It may not be as sexy or beautiful as muddy cob, or Swedish spruce or pine. All the same, it feels appropriate that even concrete can borrow from the earth’s bounty, and like the Skellefteå tower, show what high ambition can achieve.