“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” This phrase, often attributed to American writer Mark Twain, is frequently used by those in the financial industry who caution about relying on history too readily for future forecasting.

Whether looking at macroeconomics, geopolitics or equity markets, there are numerous similarities market participants are pointing to today. History is a useful guide when navigating financial markets, but it is important to recognise the nuances and differences and remember that past performance is not a guide to future returns.

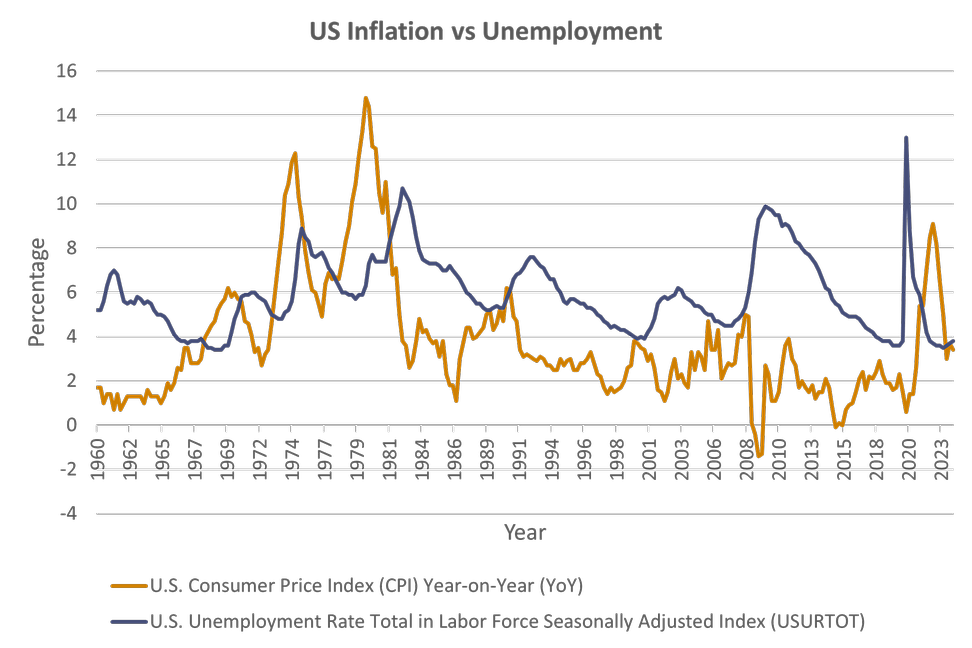

Take the macroeconomic picture. In the 1960s, the Vietnam War led to a substantial increase in US government spending on military operations and equipment, which sent the budget deficit ballooning. This loose fiscal policy helped push unemployment to very low levels, which preceded oil shocks in the 1970s. These multiple shocks sent inflation surging, resulting in interest rates rising to double digits, and rippled through the economy. The so-called Great Inflation period was a time of significant economic upheaval due to stubbornly high inflation, stagnant economic growth and elevated unemployment levels.

It’s easy to draw parallels to today. Conflicts in the Middle East and Russia/Ukraine have led to a spike in oil and energy prices. Unemployment is at record lows and the labour market remains extremely tight, while the government engages in loose fiscal policy reminiscent of the time nearly half a century ago. We believe the Federal Reserve (Fed) has learnt the lessons of the stop/start interest rate policy of the 1970s, which contributed to the dual inflation spike seen in 1973 and 1979.

While most said the recent events in the Middle East would be contained, the US and the UK have been drawn in, given the Houthis’ attacks on shipping vessels in the Red Sea, which pose a threat to the free movement of goods in one of the most crucial shipping lanes in the world. Drone attacks on a US military base in Jordan have led to the US expanding military operations in Syria and Iraq. Investors are watching events unfold with growing concern and remain worried the conflict could escalate further.

Equity markets are also experiencing “déjà vu”. Valuation levels of some of the artificial intelligence (AI) companies rival the euphoria not seen since the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s. At the time, it was companies such as Yahoo, Microsoft and Pets.com that led the charge. (It may be too late to Ask Jeeves what he thinks of ChatGPT!). Furthermore, the concentration of the so-called Magnificent 7 stocks means the market-cap weighted S&P 500 Index is the most concentrated since the 1970s.1

Indeed, we must be mindful when trying to forecast investment outcomes based on historical events. Take, for example, the stark change in demographics. In the 1960s, the baby boomers came of age and entered the workforce. This generation have now retired and are putting pressure on government budgets - not only are they drawing on their pensions, but they are putting strain on medical budgets. Given the shocks from the pandemic, it is likely baby boomers will likely want higher levels of savings to see them through retirement given stretched medical systems.

Furthermore, demand for care homes, and consequently care workers, is likely to remain high due to staffing shortfalls. This poses a conundrum for central bankers who remain alert to wage pressures amid the historically tight labour market. Baby boomers are also most likely to own their houses outright, so are therefore able to benefit from high interest rates. This dynamic explains why the sharp rise in interest costs has not slowed the economy as much as some had predicted so far.

On the other hand, the overall cost of living and changing priorities have led to declining birth rates across most developed nations including the UK. Home ownership plans have been delayed given affordability challenges. Recent census data shows that home ownership has dropped over the last decade in England and Wales, while the number of renting households has increased.2

This paints a vastly different demographic picture today than 50 years ago, and with it comes widely different investment implications. As financial professionals, we can draw on history to learn lessons, but it is crucial to use these past events as a guide rather than a strict roadmap that must be followed.

[1] JPMorgan, Global Markets Strategy, 30 January 2024

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.